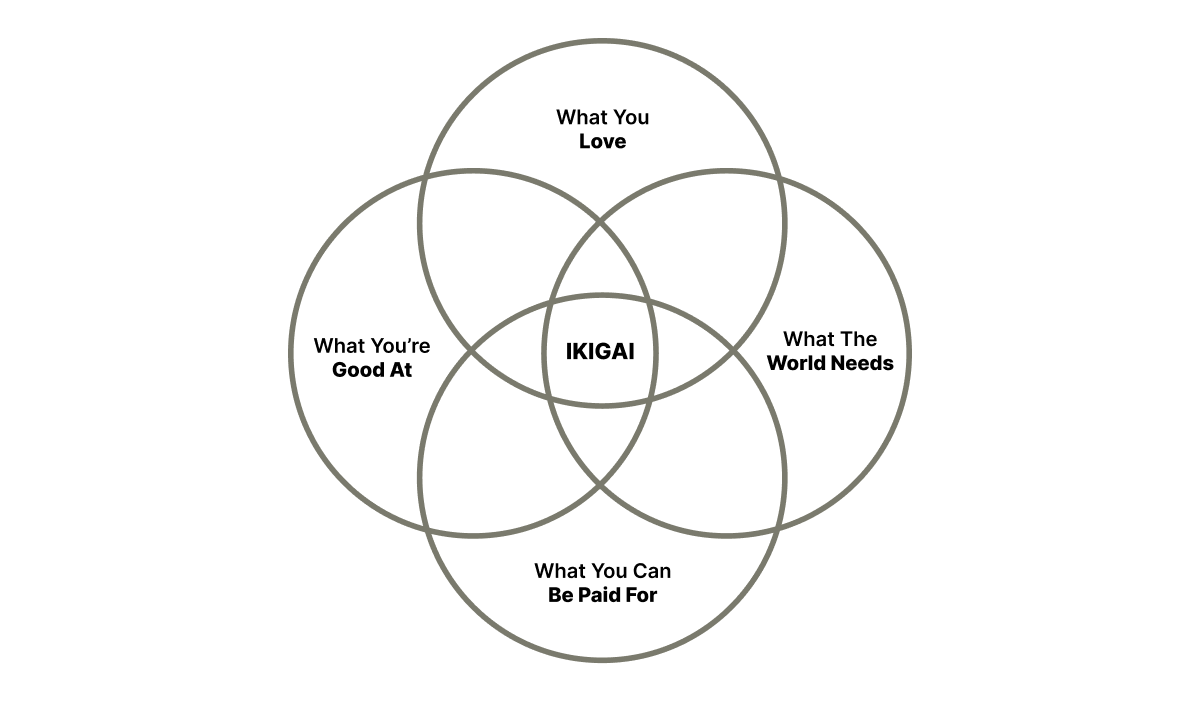

The first time I came across the Japanese word Ikigai was through this widely-circulated Venn diagram:

You may have, too.

And for a while, I carried this definition until I dug deeper into the philosophy while researching for my book, Kokoro.

While the diagram and the Westernised version of this Japanese concept aren't entirely off the mark, they don't capture the raw essence of Ikigai and instead aim to offer us a diluted framework to fit in.

In this blog post, I'll talk about how the popular definition of Ikigai is constraining and harder to access, what the actual definition is, and share examples and ideas to figure out what Ikigai means to you.

Let's begin by understanding:

What’s wrong with the Venn diagram

Philosophy is a subject that's vastly open to interpretation.

You and I could read the same chapter from Lao Tzu's Tao Te Ching and interpret it differently, biased by our past experiences and worldview.

While I can't be definitive about how the popular definition of Ikigai came into existence, I can make an educated guess that it resulted from interpretation differences.

The definition you may have seen making rounds on the internet and in numerous books goes something like this:

Ikigai is finding something we're good at that helps people around us and which could be monetised.

In other words, it's about doing something you love that feels meaningful and getting paid for it.

The problem with this templated definition is that it limits our options regarding what our Ikigai could be.

Ikigai is broader and more accessible than that.

The original meaning of Ikigai doesn't burden us with any financial or social pressures, as advertised in the popular interpretation.

You don't have to convert your hobby or passion into a cash machine or find a job you love and would do regardless of the associated salary to experience Ikigai.

But rather:

Ikigai is what makes life worthwhile

Wait, what?

Isn't that what the Venn diagram was trying to tell us?

On the surface, yes, but when you go beyond that, not exactly.

For starters, what makes life worthwhile to you might differ from what you can work on and produce something valuable enough to make a meaningful living.

You might feel the liveliest when you fold and fly paper aeroplanes, read comic books or write poems. And while you can arguably earn some money out of these activities, often, it's not enough to make a livelihood, or it isn't a recurring source of income.

But even if it is, we all know how turning a hobby or any activity we enjoy into a business can make it feel like a job — and, ironically, less worthwhile.

Also, there are activities that might be worthwhile to you, but you can't monetise them. Like caring for your family, hiking a trail for personal satisfaction, playing games with your friends or imparting wisdom to your children and shaping their lives.

These are all meaningful things that make us human and enrich our souls, but we won't necessarily be turning them into a business.

Moreover, as you age, your ability to earn an income through your Ikigai might decline. Does that mean you lose your Ikigai as you grow older?

This is where the raw meaning of Ikigai makes it more accessible to us.

Without the pressure to monetise and have a social purpose, your Ikigai doesn't have to be grand. It can be anything that makes you feel alive and excited to see another day on this planet.

You can be a baker at work, but your Ikigai could be sharing insights about your city and your culture with foreigners through a blog or in-person meetings.

Another person might be a banker by profession, but their Ikigai could be growing tomatoes in their backyard to make homemade pasta sauce in small quantities for personal use and friends and family — with no pressure to turn it into a mass production job.

When you interpret Ikigai like this, it's much easier to approach and experience.

But monetisation and social usefulness don't have to be a taboo.

I have questioned myself many times, and every time, I've received the same answer: writing is my Ikigai.

For some reason that I haven't entirely uncovered, I love writing. I just do. And I would happily pursue it even if I didn't get paid.

In my nearly 18 years of writing, most of it was purely out of love for this craft and because it made me feel good and excited.

In those 18 years, I have graduated in my primary role many times, from school student to engineering graduate and finally a working software professional, but writing has always been a part of me that stayed.

Last year, after writing on the side for close to two decades, I decided to make this a full-time thing.

Not for it to transform into the popular definition of Ikigai — a purpose that pays. But to have more time and space to dedicate to this activity I dearly love.

I know this makes it seem like we're back to square one — pursuing something we're good at and getting rewarded for it — but monetisation and any social impact from my writing are a plus, not a necessity.

I don't imagine myself not writing anymore if I switch to another mode of income, say software development or some other business (or maybe take a boat to Monte Cristo to dig up that treasure). As far as I can see, I'll probably write something for the rest of my life.

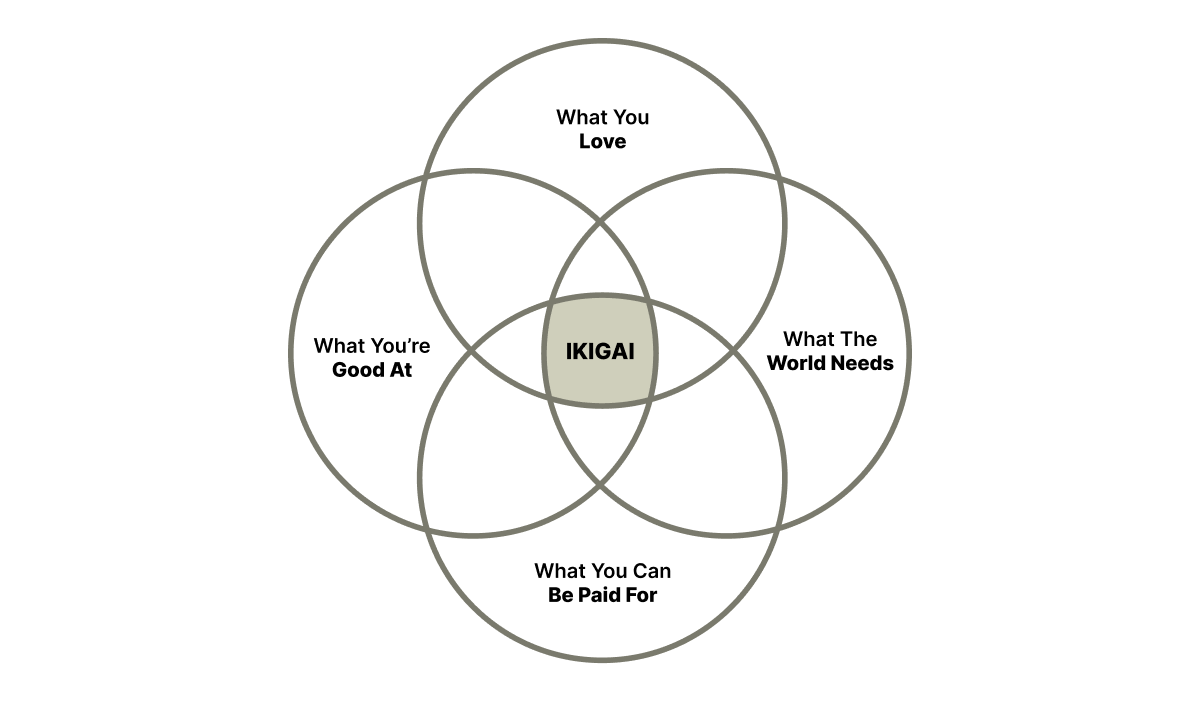

Therefore, although the Venn diagram and the popular definition aren't entirely wrong, your Ikigai doesn't have to be at the intersection of all four circles as in the diagram:

It can just be something personal that makes your life worthwhile without lofty ambition or financial pressure.

Moreover, your Ikigai doesn't have to be this one grand purpose you commit to for life. It can grow with you.

For example, when you become a parent, your Ikigai could shift from photographing wild birds to being a caring parent. You can still have the same career and hobbies with a renewed Ikigai.

Kokoro

Enjoying what you've read so far? You'll love the book I wrote on 31 timeless Japanese philosophies like this one.

Get Your CopySo:

How do you find it?

I don't know of a time-tested framework that will magically reveal your Ikigai in a snap. However, based on my interpretation of this concept, I can offer a few introspective questions that might help.

First, forget about the standard Venn diagram and cast aside any societal impact, financial opportunities and even the requirement to be good at your Ikigai.

Then, ask yourself a couple of these questions:

- What makes me genuinely happy, fulfilled and lively?

- What makes me keep going even when life seems challenging or depressing?

- What makes me excited without any external motivation?

It's okay if you don't have a clear answer right now. That's what our subconscious mind is for.

When I hit a wall like this, instead of badgering myself to find an answer I can't seem to put together, I plant the idea or a question in my mind and let the answer bubble up naturally.

Forcing yourself might get you an answer, but it might not be authentic.

Be patient and observe your actions; you'll likely have your answer floating up serendipitously after a while.

Finding our Ikigai is one of the greatest joys in life because it gives us something to live for, even in our darkest moments.

Find yours if you haven't already.

In-depth articles, series and guides

In-depth articles, series and guides